Tolerating two years of a pandemic in no easy (but some manageable) steps

First off, a reminder: Don't listen to random or not-so-random people like me when it comes to predictions about the spread and danger of COVID-19. Listen to the epidemiologists. I suggest starting with:

Background: Social distancing, isolation, and all the rest can save a lot of lives. Don't take my word for it, read the ICL report.

But when you read that report, you'll notice something interesting. It's possible that when we try to finish the big part of social distancing, the virus just returns nearly as bad as before:

I'm going to argue that we'll get through that, because of substantial changes we'll be able to make over the medium term to handle it. Some of this is taken from a series of tweets from me a week ago, is further bolstered by tweets from Trevor Bedford, and includes some material beyond that.

- The Imperial College London team, who've done groundbreaking work on previous coronaviruses including SARS and MERS. It's an experienced, all-star team.

- Trevor Bedford's twitter feed is full of great stuff tracing the path of the coronavirus in Seattle.

- Adam Kucharski et al. at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine;

- The work from Christian Althaus's group at the Institute for Social and Preventative Medicine

- Helen Branswell's reporting on the subject is accurate and lucid.

Background: Social distancing, isolation, and all the rest can save a lot of lives. Don't take my word for it, read the ICL report.

But when you read that report, you'll notice something interesting. It's possible that when we try to finish the big part of social distancing, the virus just returns nearly as bad as before:

|

| Figure 3A reprinted from the ICL report. |

Why will this get better, and when?

Advance 1: Testing

Over the coming weeks to months, we're going to make reasonably good progress in increasing the ease of testing. The US got off to a terrible start on this, which has crippled our ability to use an isolation-based strategy, but eventually, things will catch up. We'll see several improvements:

Testing phase 0: Insufficient testing to even measure a substantial fraction of cases. It's reasonable to estimate that as of a week ago, the US had 10x more cases than we were able to measure. Just a week ago, the state of Pennsylvania had tested 252 people, identifying 47 positives. Today, we've tested 4137 people, finding 371 positives. To put that in context, the state has about 12 million residents, so we've tested about 1 in 2900 people. At the outset, testing latency was about 3 days to get results. Some tests now have the latency down to a matter of hours.

Testing phase 1: Sufficient testing to measure the true prevalence of cases and test all reasonable possibilities. We're probably going to reach this phase while we're still in a "lockdown" state, so it won't make things easier, but it's a necessary step to being able to exit complete lockdown. Without accurately understanding the local and national prevalence of the disease, we can't make good decisions.

Future advance: Serum antibody tests to tell if someone has already had the disease. This may be particularly important for health care workers, food chain workers, etc. We don't yet have hard data on how immunity behaves with COVID-19, but it's reasonable to think there will be some for at least a limited period of time. Once you've had it, you're probably clear to go back to work. There may be people who had low-symptomatic or asymptomatic cases who we can clear but didn't test (see above), so a serum antibody test that can measure whether you've been previously infected can be valuable for helping repopulate the workforce, particularly for some of the highest-risk jobs. [Example: Health care workers are at substantially higher risk of contracting the virus].

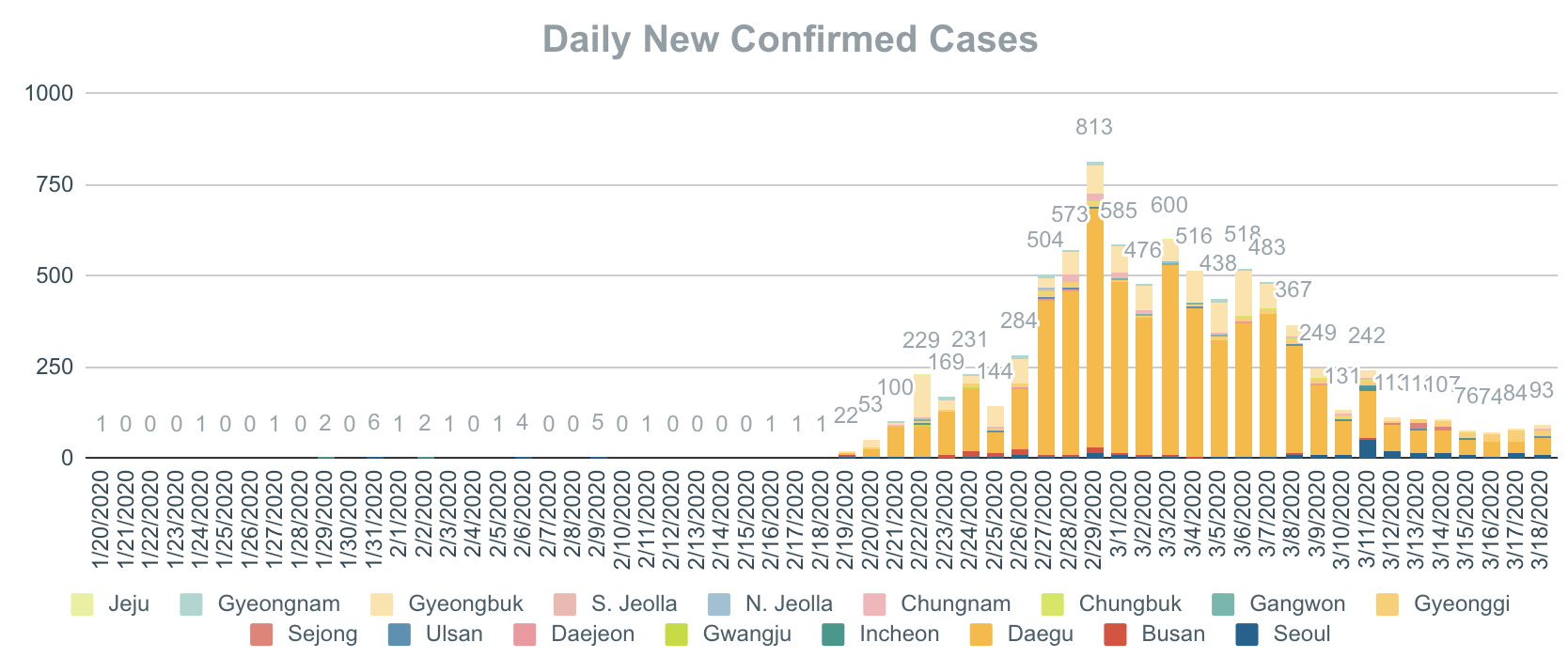

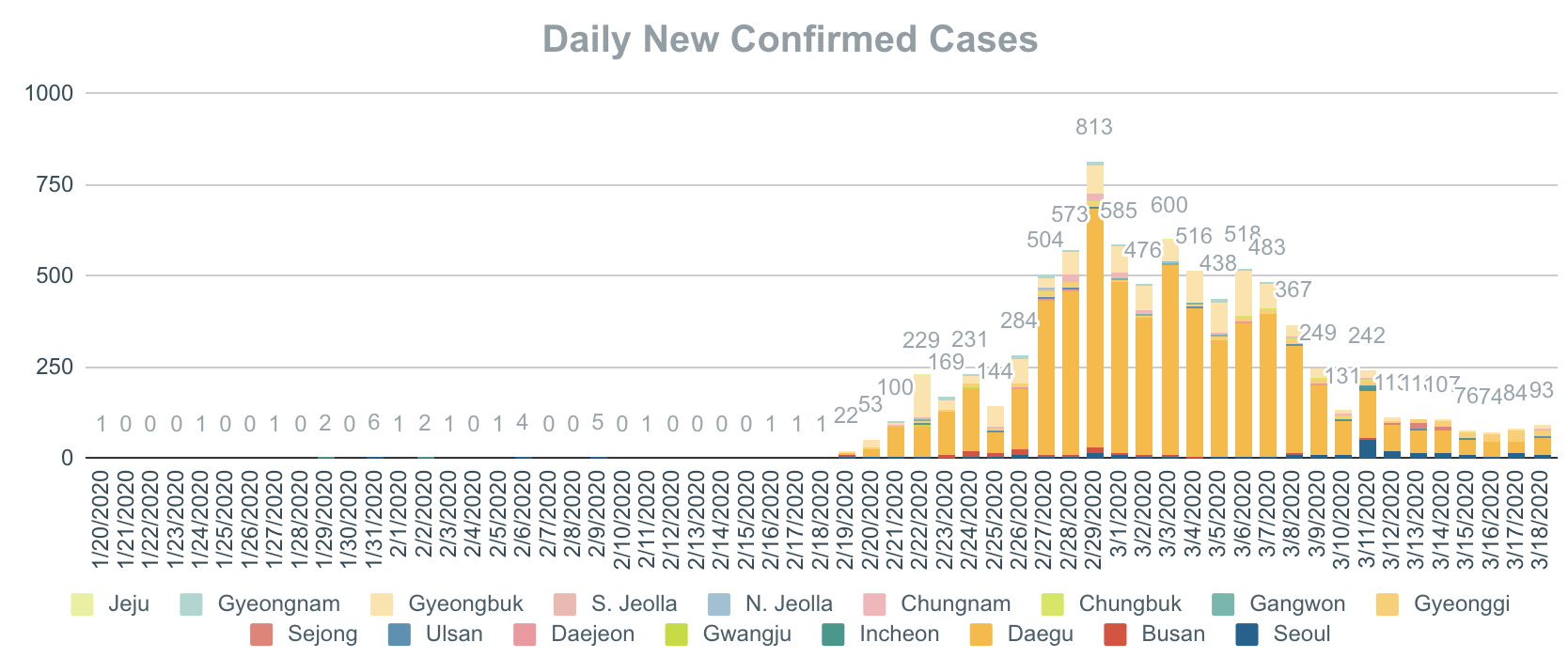

Future advance: Widespread, cheap testing akin to that in Singapore and South Korea. When people with nearly any symptoms can get tested, it may become possible to engage in much more careful isolation of confirmed cases, while allowing more limited interaction between the healthy, combined with aggressive contact tracing. Trevor Bedford's tweets laid this out well, but South Korea's success in containment is a good example of this, keeping in mind that there is still very substantial restriction on contact there:

Future advance: Cheap testing at home. If it's possible to test every member of your family daily, we can probably let people go out on their business much more than we can now. This obviously requires substantial cost-reduction and throughput improvement of the testing, and seems farther off than the previous two.

tl;dr: As testing gets better, we can relax some of the social restrictions. Not all of them, but it opens a middle ground between "don't leave your house" and "go hang out with 5000 people from around the globe at a conference in Boston." Getting to such a middle ground is important for the livelihood of local businesses, particularly those that can't change to remote or delivery models. Resuming, e.g., operating a house cleaning business at the cost of requiring daily coronavirus tests may be feasible, particularly if the tests were free and could be done at home.

Want more? See this Wired interview with Larry Brilliant, an epidemiologist who helped eradicate smallpox.

Want more? See this Wired interview with Larry Brilliant, an epidemiologist who helped eradicate smallpox.

Advance 2: Supplies

One of the reasons we need to flatten the curve is that we have limited supplies of hospital beds, medical personnel, personal protective equipment, and ventilators. Over time, we can begin to address some of these issues.

It takes a while to ramp up manufacturing, even of seemingly simple things like masks. For critically-needed supplies such as masks/PPE and ventilators, we should expect to see two increases in our manufacturing capacity:

Increase 1: Increase the throughput of existing lines by increasing the duty cycle. By hiring more workers (assuming that the inputs are available), some manufacturers will be able to increase throughput by working additional shifts, up to the point that equipment is running full-time. (Full time, of course, is limited by downtime needed to maintain the equipment, so very little actually runs at a 100% duty cycle.) For example, Medtronic announced that they were moving to 24/7 production of ventilators at their existing facility in Ireland. Similar increases are happening with mask manufacturing and the other equipment components we need. This is the fastest way to increase production, but it's limited: Very few lines were probably running at less than shift per day (~30% of capacity), so we won't get more than a 3x increase in production this way. But that still helps.

Increase 2: Add more manufacturing lines. Depending on the complexity of the process, building a new line could take from weeks to many months. In some cases we can convert existing lines: Some sewing facilities in China have rapidly switched from clothing to masks, but there are bottlenecks farther up the line, such as the melt-blown fabric fabricating machines that may take five to six months to build. While Hanes has rapidly turned around to manufacture masks, they're only able to make three-ply cotton masks, which are less effective than conventional surgical masks. Ventilator manufacturer Ventec estimates they could go to 5x ventilator production in 3-4 months. If we ballpark that increasing global critical supply production capacity by a factor of ten will take a year, we're probably in the right range.

The return on this investment is somewhat limited, because it also takes trained personnel to operate ventilators, but we get good advantages from them nonetheless:

- Sufficient PPE for health care workers increases the number of available (i.e., not out sick or quarantined) skilled workers;

- Reducing the chances of health care workers spreading the disease to themselves or vulnerable populations is an important part of mitigating the ICU cost of coronavirus cases;

- Having sufficient masks of any sort to create a general culture of mask-wearing in the US is likely to reduce transmission, allowing more going out-and-about at the same transmission rate, particularly in high-density areas such as New York.

This doesn't buy us unfettered movement, but it lets us tolerate a higher active number of cases at any given time -- i.e., means we don't have to flatten the curve quite as much to achieve the same savings of life. Not having to flatten as much later means that we don't have to impose as many restrictions on people's lives and ability to make a living.

Advance 3: Treatment

The more COVID-19 cases we treat (particularly when we have some breathing room to be deliberate about it), the more we learn about how to do better with future cases. This too will come in several phases:

Phase 1: Best practices. Easy to develop and fast to communicate, improvements in best practices for management of patients with COVID-19 can help improve the survival rate and reduce hospitalization times. There's no silver bullet here, but it's cheap. Examples of this include the development of specialized drive-through testing, which minimizes patient-to-patient and patient-to-provider contact. More technical examples include the WHO's continually-updated best practices for clinical management of COVID-19 cases.

Phase 2: Pharmaceutical interventions. There's a lot of breathless discussion out there about whether or not particular drugs or drug combinations can help reduce the extent of symptoms of COVID-19 (or, similarly, the back-and-forth about whether NSAIDs are harmful). The reality is that it's very early for all of these and that it will take substantial more study before we have solid answers. An example is the ongoing evaluation of chloroquine combination therapy. We don't have anything yet, but we're likely to find things that help. This help likely won't be a panacea either - consider that the most effective antiviral we have against influenza decreases symptoms by about a day - but every bit helps in combination with the other bits.

Phase 3: A vaccine. Depending on the efficacy and side effect profile of the vaccine, this could be the end of the discussion, or it could simply massively reduce the cost and deaths associated with the virus. But most experts concur this is 1-2 years out.

Treatment has the same effect as fixing supply limitations: We can tolerate more active cases at a time, i.e., we can lower the cost to people's lives and jobs while keeping as many people from dying.

Advance 4: Societal Changes that Reduce Contact

There's a lot of important face-to-face interaction in society, but there's a lot we can get rid of, and we're about to have several months of experimenting with what we can and can't change easily. As a warning, this is the least-baked of everything I'm saying here.

Take, as an example, three models of grocery shopping:

Model 1: Conventional US shopping. Each customer goes to the grocery store weekly (or whenever). At the grocery store, that customer comes into contact with many of the workers present in the store, as well as the other people shopping at the same time.

Model 2: The Instacart Model. A specialized delivery service sends shopper/drivers to the store who do the shopping and deliver groceries to the customer. An instacart driver can probably do in the range of 5 shopping trips per day. Over the course of a week, then, this shopper/driver reduces the number of contacts that store employees experience by a factor of 25 (5 replaced shoppers per day). A typical grocery store has in the range of two thousand customers each week, putting every employee in contact with hundreds of different people. Moving to model 2 reduces that substantially, but there are still a large number of different shoppers entering the store each day.

Model 3: Store shoppers shop, drivers drive: In this model, a customer order is picked and packed by employees of the store itself. The store employees then transfer the packed groceries to a driver (who never enters the store and can pick up the groceries from a distance). The driver drops the groceries at the customer's house. In this model, drivers never have customer or employee contact, and thus never act as a disease conduit from other people to store employees or to customers. Store employees still come into contact with each other regularly, but it's far better to have regular contact with the same smaller group than to have a much larger contact graph.

Other areas may go completely online. Consider that today we have the NASDAQ, an entirely electronic exchange, and we have the NYSE, where traders -- until three days ago -- would physically cluster in a cramped environment. The NYSE has temporarily gone electronic-only (which probably won't change much), and I suspect it won't go back.

This great collective experiment we're doing in remote-everything is likely to yield other changes that let us continue to get things done with reduced chances for viral transmission and/or travel. When this is all done, I'm not going to fly to another in-person program committee meeting to referee scientific papers. I'm done with it - I love my colleagues and love the opportunities to chat research, but it's unnecessary travel and by the end of this we'll have perfected on-line paper discussions and program committee meetings.

I don't want to paint too happy a picture for this. There are changes that are going to be absolutely destructive to people's jobs and income -- unemployment claims are skyrocketing, and industries such as hospitality are going to be very, very deeply hurt, and these are things that won't be fixed by modest social changes. That's going to take concerted government response at a scale we haven't seen since the great depression. There are other people for whom the critical nature of their jobs, from food production to healthcare, will require them to continue working with other people and suffer an increased risk of catching coronavirus, and we we need to ensure there's support in place for them. But there are things that will improve life for all of us as we make it through this pandemic, and we get the most benefit from them if we can minimize the spread of the disease for a period of months.

As more people have passed through the disease and gain immunity, as we roll out more and more testing, as we reduce the case fatality rate through better interventions, and as we reduce the amount of "low-importance" social contact, we'll be able to increase the amount of high-value social contact we allow ourselves. But with the extent of spread in the US already, this is likely to be a game we play out over months to two years, with possible seasonal ebbs and flows. But we'll come through it better-equipped to handle future pandemics (and reduce the chances of them going pandemic).

Comments

Post a Comment